photo: Jaroslaw Praszkiewicz

The genesis and course of the Nazi persecution of Roma and Sinti

Extract from "The Destruction of European Roma in KL Auschwitz: A guidebook for visitors"

The roots of the Nazi persecution of Roma and Sinti can be found in xenophobia which Roma have experienced since the beginning of their presence in Europe, but most importantly in the radical change of the perception of this group, which can be traced back to the beginnings of the modernization of European societies in the 17th-18th centuries and which was associated with the emergence of the ideology of antigypsyism. In accordance with this ideology, Roma and Sinti began to be treated as people who by their very existence subverted the values of modern culture. Their way of life became in the dominant culture a synonym of otherness and backwardness, a “social problem” or “pathology” which needed to be eliminated by means of forced assimilation. In the course of time, however, the Roma culture and way of life started to be perceived as biologically conditioned and Roma/ Sinti as a different, inferior race, the features of which could be changed by assimilation. This was the beginning of the process that led to the genocide committed against Roma and Sinti.

The situation of Roma and Sinti after Hitler’s seizure of power in Germany was a result of several overlapping processes: (1) the intensification of the way the already existing discriminatory regulations were implemented, which led to increased control of Roma and Sinti by the authorities; (2) the limitation of both the opportunities to live a traditional Roma life and those for integration with the life of majority; (3) the large scale employment of scientific procedures of registration and classification; (4) the introduction of new legal regulations directed against Roma and Sinti, based on racist ideology and leading to their exclusion from society. The situation of Roma and Sinti in other European countries was similar, particularly in those in which the modernization process was advanced.

In Nazi Germany, elements of racist discourse occurred more and more frequently in the legislation, and was already commonly present in the official statements of Nazi officials. The racist nature of the anti-Roma regulations was clearly present in the sterilization program that had been developed in the 1930s. The program was associated with eugenics—the notion of improving society by means of steering natural selection—and originally targeted the physically or mentally impaired. Soon however, together with the development of the racist ideology, the program of sterilization involved Roma and Sinti. Sterilization was the first step on the way to genocide.

In connection with the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, it was forbidden for Roma and Sinti to be married to “racially pure” Germans, and their basic civil rights were limited. The limitation of the rights of Roma and Sinti was, however, a gradual process, which meant, for example, that in the years 1940-1941 they could still be drafted into the German army.

Because of the racist ideology behind the persecution of Roma and Sinti, it was necessary to create an institution in charge of “racial research” which supported anti-Roma actions and policies. Such an institution was created in 1936, and from 1937 it bore the name of the Research Institute for Racial Hygiene and Population Biology, and was headed by Dr. Robert Ritter.

An important aspect of the Institute’s activities was the construction of racist criteria for defining Sinti and Roma and assigning them to the appropriate categories. According to one of the several definitions elaborated by the Institute, it was enough that one of the great-grandparents of a given person was classified as a “Gypsy” for that person to be classified as belonging to the category of “mixed blood Gypsies” with 1/8 of “gypsy blood” and so be subsequently subjected to repression.

The racial criterion as a reference point for the policies towards Roma and Sinti was formulated precisely in the “Decree for combating the Gypsy Plague” of December 8th, 1938. We can read in this document that the right method for solving the “Gypsy question” was to treat it as a racial problem. In the contemporary juridical practice of the Federal Republic of Germany, the date of the Decree is taken as the beginning of the official persecution on racist grounds, which means that Roma and Sinti who were subjected to persecution after that date have the right to be compensated.

The outbreak of the Second World War meant for the German Sinti and Roma the next stage of exclusion from society – deportations. These took place in May 1940: ca. 2,800 Sinti and Roma were deported to occupied Poland where they were placed in the Jewish ghettos or labor camps. Later the deportations were stopped, in part because of negative feedback from the unprepared authorities of the occupied territories. Some deportees managed to escape and return to Germany. Those remaining were killed in the wave of mass killings in 1943.

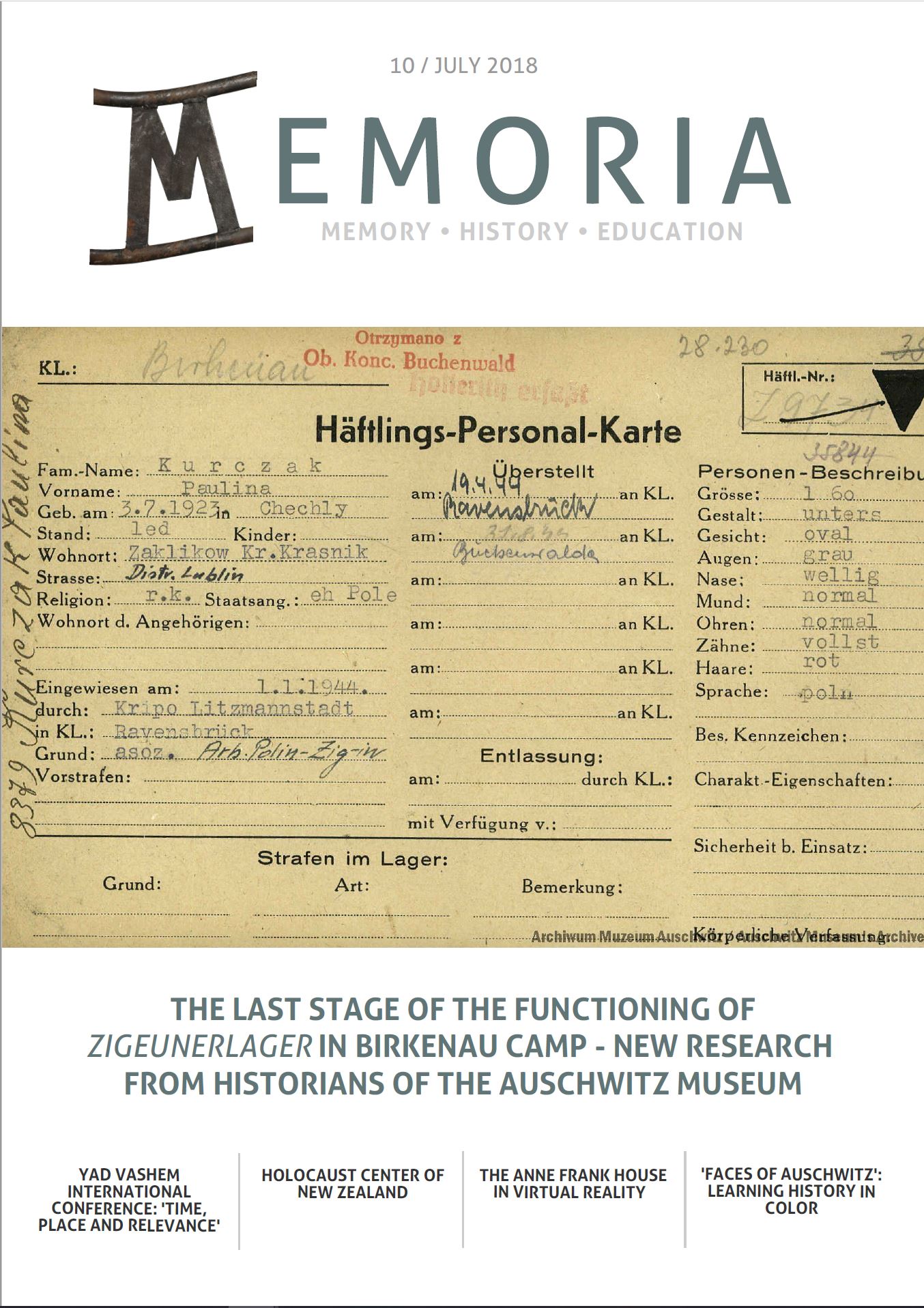

The second great deportation of Roma and Sinti to the area of occupied Poland took place in November 1941. This was part of the so-called “action of cleansing the eastern districts” administered by Adolf Eichmann. The victims of the action were Austrian Roma and Sinti. Altogether, approximately 5,000 persons were deported from Austria and placed in a separate part of the Jewish ghetto in Łodź (at the time of German occupation renamed Litzmannstadt). Approximately 600 persons died there as a result of a typhoid fever epidemic and inhuman living conditions. The others were transported to the Kulmhof death camp where in the beginning of January 1942 they were gassed in trucks specially adapted for the purpose.

The destination of the third and largest wave of deportations of European Roma and Sinti was KL Auschwitz. Its basis was created by the so-called “Auschwitz order” (Auschwitz-Erlass) issued by Heinrich Himmler on December 16th, 1942. The organizational details of the deportation were agreed upon during a conference that took place on January 15th, 1943 at the Reich Main Security Office in Berlin. This conference is perceived by some scholars and Roma activists as a counterpart of the Wannsee conference which a year earlier had sealed the annihilation of the European Jews. Roma and Sinti were to follow.

KL Auschwitz was the main place of extermination of Roma and Sinti in occupied Poland but they were also murdered in other camps: Kulmhof, Treblinka, Bełżec and Sobibór. Roma prisoners were also sporadically murdered in concentration camps such as Buchenwald or Ravensbrück.

Probably the second largest center of the extermination of Roma was the Jasenovac camp, set up by the Croatian government of Ante Pavelic, allied with Nazi Germany. The killing of Roma in Jasenovac was exceptionally cruel. Shooting was preceded by tortures and rapes, and victims were also murdered with sticks and knives. One cannot estimate precisely the number of Roma victims in Jasenovac: according to the recent findings of Croatian historians there were approximately 16,000 , almost all Roma in the Croatian fascist state were murdered.

The victims of KL Auschwitz were mostly Roma and Sinti from the Reich (including Austria) and from the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. It is estimated that 70-80 percent of Roma and Sinti from the Third Reich perished, and even more of those inhabiting Bohemia and Moravia. The third group of Roma victims of KL Auschwitz were Polish Roma. In general, during the Second World War between 8 and 13 thousand Polish Roma perished, comprising approximately one-third of the Roma population of the country. These data, however, are very imprecise.

Most of the Polish Roma as well as those from the Soviet Union perished in mass killings perpetrated by the units of German Police, Wehrmacht and SS, particularly by the so-called Einsatzgruppen, sometimes assisted by the local Police.

In the occupied area of the Soviet Union the systematic genocide of Roma was carried out mainly in 1942. In the zone occupied by the Army Group North, the fate of the Latvian Roma was particularly tragic: almost half of this community of ca. 4,000 people was killed. Also Roma who lived in the area of activities of the Army Group Middle suffered great losses. That area was characterized by a large concentration of Roma because it was there, mostly near Smolensk, where Roma collective farms had been established, the showpieces of the early stage of communist policies regarding national issues. The area of Army Group South could be divided into eastern Ukraine where probably the biggest mass shooting of Roma occurred: in August 1942 almost 2,000 Roma from Chernihiv and its vicinity were murdered, and in Crimea where ca. 70 percent of the Roma population perished.

In German-occupied Serbia, Roma from the very beginning of the occupation were arrested and sent to work as slave labor. Like the Jews, Roma were also victims of the so-called reprisal executions in which 100 hostages were murdered for every German soldier killed by partisans. According to some sources, the number of Roma victims in Serbia can be estimated at 20,000. Many Roma, how- ever, managed to escape and join the resistance.

In the areas of the former Yugoslavia under Italian (Montenegro, part of Slovenia) or Bulgarian (Macedonia) occupation Roma generally were not persecuted although they could be sent to internment or labor camps. The situation of Muslim Roma from Bosnia, controlled by the Croatian state, was similar.

In the occupied countries of Western Europe the fate of Roma varied. In France they were interned in special camps while those Sinti and Roma arrested in Belgium could be deported to concentration camps in Germany or to KL Auschwitz where most of the Dutch Roma also perished.

The situation of Roma and Sinti in the countries allied with Nazi Germany (except Croatia) was very differentiated. In Italy they were forced into internment camps. In Romania, approximately 25,000 Roma were deported to the area of Transnistria where most of them died of hunger and disease. The majority of the Romanian Roma community of 200,000 were, however, not affected. Bulgarian Roma, like Bulgarian Jews, avoided extermination but could be sent to various public works. In the Slovak State Roma men were often sent to labor camps in which the conditions of existence were very harsh. In 1944, after the outbreak of the Slovak National Uprising, some of the labor camps were transformed into concentration camps in which many Roma died of disease or were shot. After the fall of the uprising, Roma suspected of participation in it could be shot or deported to the concentration camps in Germany. In Hungary, the organized persecution of Roma started in 1944 when the Hungarian fascists (the Arrow Cross movement) came to power. They sent Roma to labor or concentration camps where many died as a result of the harsh conditions.

The general number of Roma victims is difficult to estimate because of the lack of precise documentation by the perpetrators, and lack of reliable statistics about Roma living in Europe before the Second World War. On the basis of the existing written sources we may speak of ca. 200,000 Roma victims. But the real number must be much higher, probably amounting to 500,000.

Sinti and Roma in Auschwitz

The last stage of the functioning of the ‘Zigeunerlager’ in the Birkenau Camp

Recent research by historians of the Auschwitz Museum

The Destruction of European Roma in KL Auschwitz

A guidebook for visitors

The genesis and course of the Nazi persecution of Roma and Sinti

Extract from “The Destruction of European Roma in KL Auschwitz: A guidebook for visitors”

Block 11

Extract from “The Destruction of European Roma in KL Auschwitz: A guidebook for visitors”

Escapes

Extract from “The Destruction of European Roma in KL Auschwitz: A guidebook for visitors”

“Zigeunerfamilienlager” (“Gypsy family camp”)

Extract from “The Destruction of European Roma in KL Auschwitz: A guidebook for visitors”

Arrival in the “Zigeunerfamilienlager”

Extract from “The Destruction of European Roma in KL Auschwitz: A guidebook for visitors”

The life of Prisoners

Extract from “The Destruction of European Roma in KL Auschwitz: A guidebook for visitors”

Children

Extract from “The Destruction of European Roma in KL Auschwitz: A guidebook for visitors”

Dr. Mengele and experiments on prisoners

Extract from “The Destruction of European Roma in KL Auschwitz: A guidebook for visitors”